Constituency Parsing for Question Answering over Linked Data

Let’s start with the goal

Given a natural language factoid question, construct an equivalent SPARQL query in order to extract the answer from a knowledge base (e.g. DBPedia). For clarity we’ll start off with a relatively complex question and go through all the processing steps of the pipeline implemented in the repo.

Who is the oldest actor that is starring in a movie directed by Quentin Tarantino?

DBpedia and Knowledge Graphs

DBpedia.org is just a frontend for a huge graph knowledge base that contains similar stuff to what’s available on Wikipedia, but in a more structured format. Let’s inspect it for a bit and try to find the answer to the question manually. The most obvious keyword in the question text is the name of director Quentin Tarantino. DPBedia has a dedicated page for the guy at Quentin_Tarantino. A bunch of information about him is available via properties - relations between a subject and an object.

- dbo:birthPlace: the place he was born in

- dbo:occupation: what he does for a living

- dbo:director: the obvious candidate for our purpose

The last one links most of the movies he directed over the course of his career. Let’s inspect Django Unchained. Again we’re faced with a bunch more info such as:

- dbo:gross: the gross profit of the movie

- dbo:director: the property that got us here in the first place

- dbo:starring: a list of actors that had a role in this movie - our point of interest

A special property is rdf:type. It gives us a list of classes an entity is part of. These classes inherit one another and form a hierarchical taxonomy. In the case of Django, some of the linked classes are:

Going deeper to dbo:Leonardo_DiCaprio we find dbo:birthDate. This could be a hint on the age of the actor - since we need to determine the oldest.

Parsers and trees

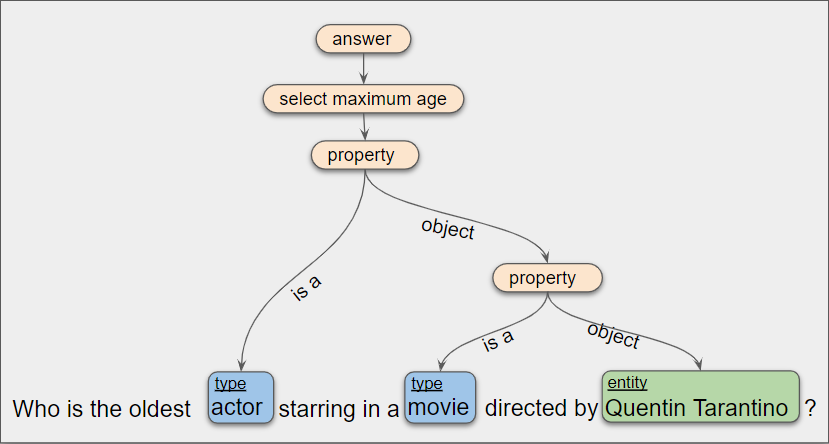

It seems there’s kind of an inherent recursive structure to our question. It could definitely be useful to try to represent it as a tree!

Obtaining this kind of a tree for text is called constituency parsing. It is typically used to understand the syntax of sentences in respect to the English grammar. But in the context of Question Answering, a custom grammar seems more appropriate. You can see the grammar I’ve created in this file on the repo grammar.cfg. It describes a set of rules - nodes in the tree, and the kind of children they can have. This tree is an intermediate representation of the query intent that is agnostic on both the input natural language (i.e. English) and the output structured query language (i.e. SPARQL).

This is similar to how a compiler’s parser works. The main difference is that it is done statistically, using a machine learning algorithm, while a compiler does it deterministically by pattern-matching and following some preset rules. Another key difference is that a question might have multiple interpretations, while a compiled code snippet generally has only one parse tree. In our case, the aforementioned grammar is only used to validate the statistically generated parse trees in order to reject bad ones.

Parsing is done using a neural conditional random fields based model [1]. The problem is first restated as labeling the question’s tokens, as described by Gómez-Rodríguez et al. [2]. The produced linear sequence of labels is then decoded using a simple algorithm. This yields the actual hierarchical structure of the constituency tree. For training this model I’ve created a dataset of almost 2000 tree-annotated questions available in constituency_annotated_questions.json. In case you’re curious how the laborious process is done (no one ever is), a tool is available in the repo here.

Nodes and resources

The neural model produced a tree, now what? Now it’s necessary to map these nodes to specific resources on DBPedia. Resources (entities, types and properties) are all uniquely identified by URLs such as http://dbpedia.org/resource/Leonardo_DiCaprio.

Entities and types

Entities are pretty straight forward to map, since there are not so many ways you can directly refer to a particular person or place. In our case the director could be referred to as Quentin Tarantino or only by his last name, Tarantino. Fortunately DBPedia has our back in this problem, since most of the entities have a list of ways they can be referred to. You can find these via dbo:wikiPageRedirects and dbo:wikiPageDisambiguates properties on a entity’s page.

Mapping entities is simply done by sifting through these lists and returning the corresponding entity URL. In case of conflicts, the most popular entity is considered. The popularity metric here is considered as the number of inbound properties for an entity. You can see this in code at entity_mapping.py

Types are mapped in a similar fashion, but wordnet-based synonyms are also used. For example, both astronaut and cosmonaut are mapped to dbo:Astronaut. In case there’s no exact mapping for the queried text, candidates are ranked using semantic similarity. You can see this in code at type_mapping.py

Properties (a.k.a. relations)

It’s all cool until you get to relations, which are way harder to map. The difficulty comes from the sheer amount of possibilities to refer to a relation via natural language. E.g. Textually expressing a movie dbo:starring DiCaprio could be done with any of the following texts:

- movies starring DiCaprio

- DiCaprio movies

- Movies with DiCaprio

- Movies in which DiCaprio plays

- Movies having DiCaprio

- A thousand more of these…

This is called Relation Extraction in literature. Luckily there are a bunch of datasets around we could leverage.

For starters, there’s PATTY [3]. It contains about 120000 patterns and their corresponding relations. However, pattern-based approaches are historically [4] not robust enough, especially since PATTY contains declarative texts, which are often too different from our interrogative texts.

Other datasets I’ve considered are:

- Tacred [5] (download link) Relatively large texts with annotated subjects, entities and the relation between. Relations follow a custom taxonomy.

- NYT10 [6] (download link) Medium sized texts with annotated subjects, objects and relations, all part of Freebase.

- Fewrel [7] (download link) Similar but with Wikidata resources.

- SimpleQuestions (download link) Not really a relation extraction dataset, but can be used with some preprocessing.

The main problem is they all represent relations of different knowledge bases: Freebase, DBpedia, Wikidata (and the Tacred custom). In order to use these for DBPedia, I’ve created a dataset that unifies cross-knowledge-base equivalent relations and organizes them in equivalence sets. This dataset was formed by aggregating other equivalency sources [8], using the owl:equivalentProperty property and by manually searching. You can see this dataset in equivalent_relations.json

Having this huge aggregated dataset and most of the relations mapped to a common set gives us the freedom to try a bunch of machine learning algorithms. Following the trend, using the BERT [9] pre-trained model and finetuning it to classify sequences as relations proved to be the most effective. We follow a paper for this step as well [10]. A relation extraction sequence for one of the nodes in our example looks something like this:

[CLS] Who is the oldest actor that is starring in a [E1] movie [/E1] directed by [E2] Quentin Tarantino [/E2] ?

The model learns to predict which relation best fits between the subject, encapsulated by [E1] [/E1], and the object, encapsulated by [E2] [/E2]. The predicted label should be dbo:director in this case. To get better results, we first extract only the possible relations given the constraints of the tree. This drastically reduces the search space. E.g. dbr:Quentin_Tarantino has about 60 properties on his page, so we only have to consider these. Using softmax as the last layer gives us the probability for each label. We can use these probabilities to rank the 60 relations, and only consider the top few.

Queries and answers

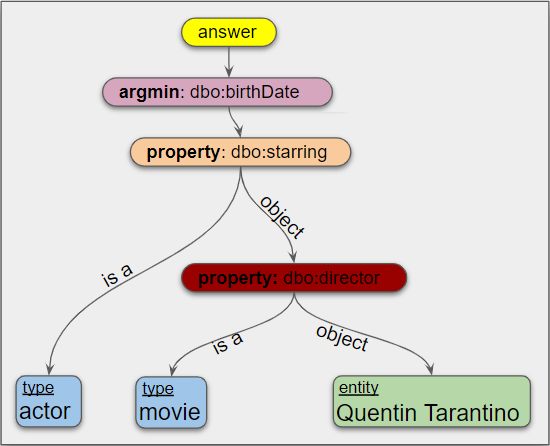

We now have a tree and the nodes are mapped to URLs. How do we get the SPARQL query and, consequently, the answer?

From now on the work is simple - no more statistics! Each node has a predefined snippet of SPARQL code associated with it. You can see these in the repo here. All we have to do is expand them in reverse order (leaves to root) and build the query incrementally. For our example, follow the color coded nodes and their respective code snippet in the final query:

PREFIX dbr: <http://dbpedia.org/resource/>

PREFIX rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#>

SELECT ?answer WHERE

{

?answer rdf:type dbo:Actor.

?answer dbo:birthDate ?b.

?a dbo:starring ?answer.

?a dbo:director dbr:Quentin_Tarantino.

?a rdf:type dbo:Film.

}

ORDER BY ASC(?b) LIMIT 1

Running this query on DBPedia’s SPARQL endpoint yields http://dbpedia.org/resource/Gordon_Liu as the answer, which is … obviously wrong (he’s born in in 1954). The query looks decent but in reality DBPedia has A LOT of data inconsistencies. The problem here is that not all actors have the type dbo:Actor associated. Removing this constraint yields http://dbpedia.org/resource/Lawrence_Tierney - born in in 1914. This is a more plausible answer. In backstage this is issue is resolved by considering more than one type. (e.g. dbo:Actor, yago:Actor109765278, yago:YagoLegalActor) etc. For the simplicity of this query, I’ve omitted them.

Results

QALD is the main competition on this problem, results on its test set are coming soon.

References

[1] Yang, J., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Ncrf++: An open-source neural sequence labeling toolkit. arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.05626.

[2] Gómez-Rodríguez, C., & Vilares, D. (2018). Constituent parsing as sequence labeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.08994.

[3] Nakashole, N., Weikum, G., & Suchanek, F. (2012, July). PATTY: a taxonomy of relational patterns with semantic types. In Proceedings of the 2012 Joint Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and Computational Natural Language Learning (pp. 1135-1145). Association for Computational Linguistics.

[4] Mesquita, F., Schmidek, J., & Barbosa, D. (2013, October). Effectiveness and efficiency of open relation extraction. In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (pp. 447-457).

[5] Zhong, Victor, et al. TAC Relation Extraction Dataset LDC2018T24. Web Download. Philadelphia: Linguistic Data Consortium, 2018.

[6] Riedel, S., Yao, L., & McCallum, A. (2010, September). Modeling relations and their mentions without labeled text. In Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases (pp. 148-163). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

[7] Han, X., Zhu, H., Yu, P., Wang, Z., Yao, Y., Liu, Z., & Sun, M. (2018). Fewrel: A large-scale supervised few-shot relation classification dataset with state-of-the-art evaluation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.10147.

[8] Azmy, M., Shi, P., Lin, J., & Ilyas, I. (2018, August). Farewell freebase: Migrating the simplequestions dataset to dbpedia. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Computational Linguistics (pp. 2093-2103).

[9] Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2018). Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805.

[10] Shi, P., & Lin, J. (2019). Simple BERT models for relation extraction and semantic role labeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.05255.